Cruelty and Control: Reproductive Rights and Health Care in the U.S. Immigration System

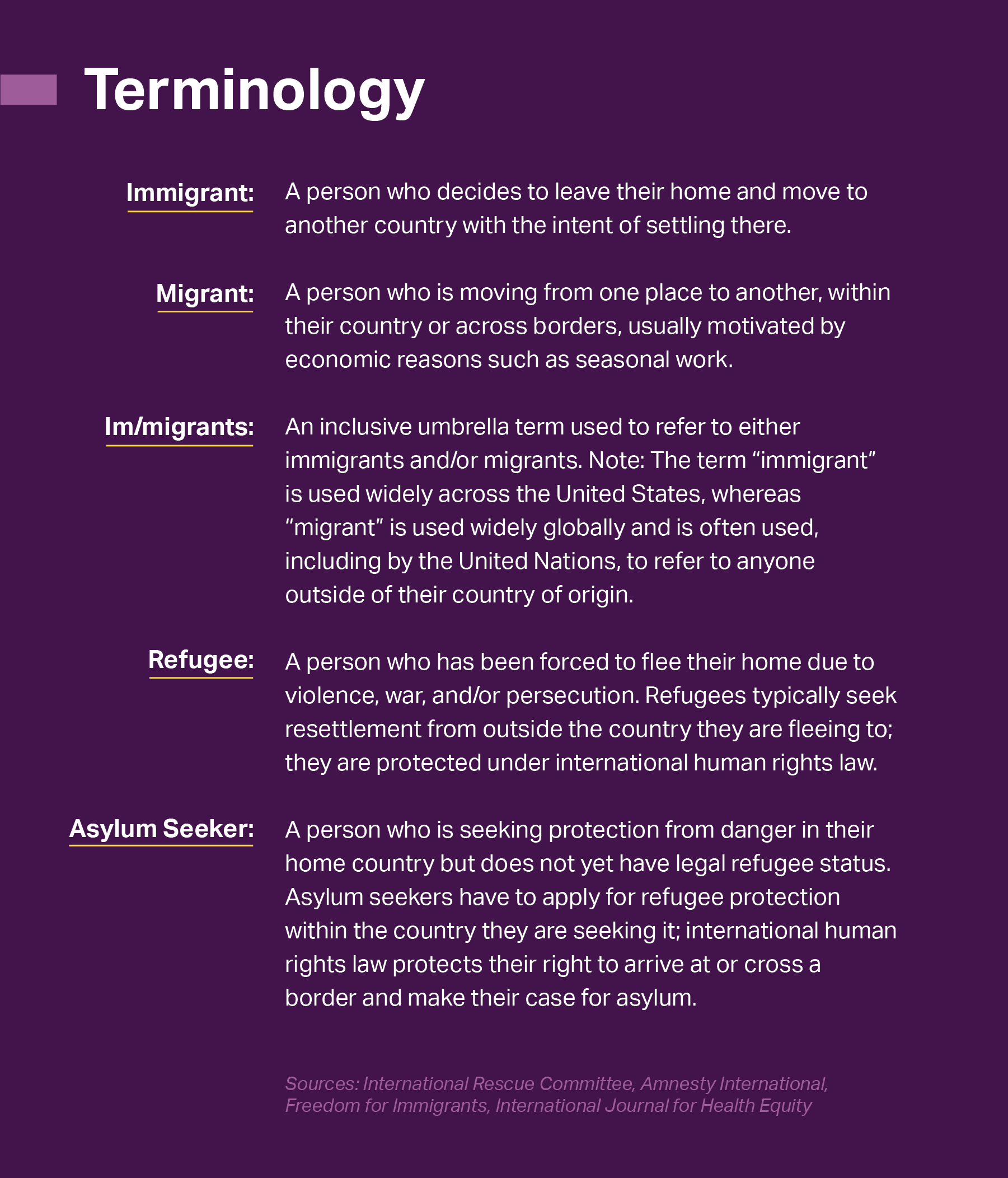

Summary

The U.S. government runs the largest immigrant detention system in the world. A far cry from America’s promises of liberty and freedom for all, this system is known for its cruelty. This cruelty is illustrated perhaps most acutely through the denial of reproductive freedom and health care for those detained in U.S. detention centers. Cruelty and Control: Reproductive Rights and Health Care in the U.S. Immigration System contextualizes current attacks on im/migrants’ reproductive rights by laying out the United States’ long and sordid history of criminalizing immigrants and communities of color, which continues from administration to administration up to the present day. In the report, we provide an overview of the federal agencies comprising the U.S. immigration system; the myriad of ways they are influencing access to, or denial of, reproductive health care, minor and maternal health care, and quality health care generally; and the depth in which these denials detrimentally affect communities of color and people who are young, LGBQTIA+ and/or undocumented. With its first report on this issue, Equity Forward hopes to elevate and add to the work of activists, advocates, researchers and truth-tellers who, for years, have been working to shed light on the inside of a system that operates with impunity. To that end, the report features original survey responses from organizations and individuals who have worked at the intersections of immigration advocacy and the reproductive health, rights and justice communities, as well as public records obtained by Equity Forward. We conclude with calls to action for transparency, accountability and reform of a carceral state that has been devastating for im/migrants seeking a better life on U.S. soil.

Introduction

America’s immigration system does not hold true to its promises of liberty and freedom for all. Many im/migrants are able to bring their dream to fruition, yet for countless im/migrants the promise of a better life is never materialized. For many, the shining facade of American justice is a veneer that masks the cruelty of our immigration system. This cruelty is illustrated perhaps most acutely through the denial of reproductive health and freedom to those detained in U.S. detention centers.

The U.S. government operates the largest immigrant detention system in the world. The system has been steadily expanding over the past three decades and today holds as many as 500,000 immigrants each year—many of whom are seeking asylum. Policies and practices blocking immigrants from everything from birth control to prenatal care to abortion have continued from administration to administration. Equity Forward’s work on this issue hopes to help illuminate the truth of this system. It is our intention to elevate and add to the work of activists, advocates, researchers and truth-tellers who, for years, have been working to shed light inside a system that operates with impunity.

This report will first contextualize current attacks on immigrants’ reproductive rights by laying out the United States’ long and sordid history of criminalizing im/migrants and communities of color. It will then present our methodology, including a survey we disseminated to organizations and individuals that have worked at the intersections of immigration advocacy and reproductive health, rights and justice communities. The words of survey participants, along with public records obtained by Equity Forward, will support the following sections of the report: an overview of the federal agencies comprising the U.S. immigration system; access to reproductive health care, minor and maternal health care, and quality health care generally; and the ways in which this denial of health care detrimentally affects communities of color and people who are young, LGBQTIA+ or undocumented. We conclude with calls to action for transparency, accountability and reform of a carceral state that has been devastating for im/migrants seeking a better life on U.S. soil.

History of Criminalization of Im/migrants and Black, Latino/x, Indigenous, AAPI and Communities of Color in the United States

In September 2020, Dawn Wooten, a former nurse at Irwin County Detention Center (ICDC), an Immigration & Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention center in Georgia, publicly shared accounts of detained people being forced and coerced into hysterectomies. Her whistleblowing shed light on mistreatment that had been well known by im/migrants and the advocacy community for years. So, it was no surprise that Wooten’s story was corroborated by first-person accounts. According to Time, more than 40 individuals submitted written testimony as part of a class action lawsuit against ICE and Dr. Mahendra Amin, the gynecologist accused of performing coerced hysterectomies and other unwanted medical procedures. The incident was a watershed moment, but it was not isolated. The cruelty of America’s immigration system is boundless.

Incidents of miscarriage linked to medical negligence and inhumane conditions within detention centers are not uncommon. Neither are reported incidents of small infants being separated from mothers, sometimes just shortly after delivery. Those seeking abortion care are outright denied or made to endure unnecessary hurdles. And those wishing to continue their pregnancies are not provided with the adequate accommodations to do so safely. Minors are separated from their guardians and families and placed with employees in a strange land who often do not speak their language. Children are separated from loved ones without adequate documentation necessary for reunification; a practice that has historical roots. The government previously undermined family structures and denied humanity when Native American children were abducted from their families to be forced into assimilation schools, and when enslaved Black families were torn apart during American slavery.

American history demonstrates that the unjust treatment of detained populations is part of a broader pattern of criminalizing im/migrants and communities of color. It is a pattern of harm that targets sexuality and reproductive outcomes as a means of oppressive control. In the late 1800s, an anti-midwife campaign, which largely targeted im/migrant and Black midwives, was intrinsically tied to anti-abortion bans spurred by a burgeoning medical profession that typically shunned non-white males from entering the field. In 1909, 1913, and 1917, California’s Asexualization Act resulted in the sterilization of thousands of Black and Mexican people—and served as a blueprint for genocide in Nazi Germany. In 1927, Buck v. Bell cemented the path for federal policy to dictate the reproductive lives of those deemed unwanted by the powers that be, allowing states to sterilize people in federal institutions. In 1929, North Carolina launched its eugenics program, which largely targeted Black residents who received government assistance; the program ran until 1974. In 1937, Puerto Rico’s government passed a law that permitted sterilization at the discretion of a eugenics board. Shortly thereafter, the U.S. government began to send health department officials to the U.S. territory to advocate for sterilization and provided U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) funding for family planning clinics housed in women’s workplaces, resulting in 33 percent of Puerto Rican women being sterilized during the 1930s and 1970s. Sterilization was so normalized on the island that it was known as “la operacion.”

In 1942, as a result of Public Proclamation No. 4, Japanese-Americans were forcibly evacuated and detained in internment camps. In 1956, women in Puerto Rico were enrolled as human subjects in experimental birth control trials. In the 1960s and 1970s, Spanish-speaking women giving birth in L.A. were provided informed consent in English or otherwise coerced and unknowingly sterilized. Also in the 1960s and 1970, many southern Black women were subjected to the “Mississippi appendectomy”—a term used by civil rights leader Fannie Lou Hamer to describe the coerced hysterectomies performed on Medicaid recipients. After the passage of the Family Planning Services and Population Research Act of 1970, at least 25 percent of Native American women were sterilized. In between 2006 and 2010, 148 women imprisoned in California came forward and revealed that they had been sterilized by coercion or without their consent. These examples are not anomalies; rather, they are characteristic of the U.S.’s long history of weaponizing law and policy against reproductive autonomy, particularly for communities of color.

The American Dream is appealing. An idea that freedom and opportunity await anyone willing to work hard seems feasible. It is this idea of liberty, justice and fairness that lures millions to America’s shores, but the reality of the American Dream is that it is a siren song. This is evident in how im/migrants have been received by the country and how their first-generation descendants are treated. It is crystalized when we look at how the immigration system treats pregnant, birthing and postpartum im/migrants. What lies behind the American promise is an immigration system that infringes on reproductive freedom, a government that separates families and a society quick to criminalize those who dare to dream for a better tomorrow.

Research Methodology

As an introductory report for Equity Forward on the intersections of immigrant and reproductive justice, we wanted to hear directly from the advocates and researchers working across the immigrant justice, sexual and reproductive health, rights and justice, detention and legal advocacy, racial justice, LGBTQIA+ rights and broader human rights spaces.

Following 10 initial partner meetings held between February and May 2021, Equity Forward reached out to 43 organizations doing this work and asked for their participation in an online survey using Google Forms. The survey consisted of six on-the-record questions about their experiences working within these spaces as they pertain to reproductive oppression as well as four follow-up questions to inform future public records research. We used a snowball sampling methodology to recruit participants; many of the organizations were referred to us by other groups we had spoken to. Six partners ended up completing the survey in June 2021, including Jane’s Due Process, National Latina Institute for Reproductive Justice and Transgender Law Center (See Appendix 1 for more details on participants).

These results, as well as our conversations with partners, guided the research and analysis of primary and secondary source documents also included in this report (including public records requests previously obtained by Equity Forward). We do not purport to have a representative sample due to the small number of survey participants; rather, we chose to intersperse the responses throughout the thematic sections of this report, highlighting the expertise of our partner organizations in different areas.

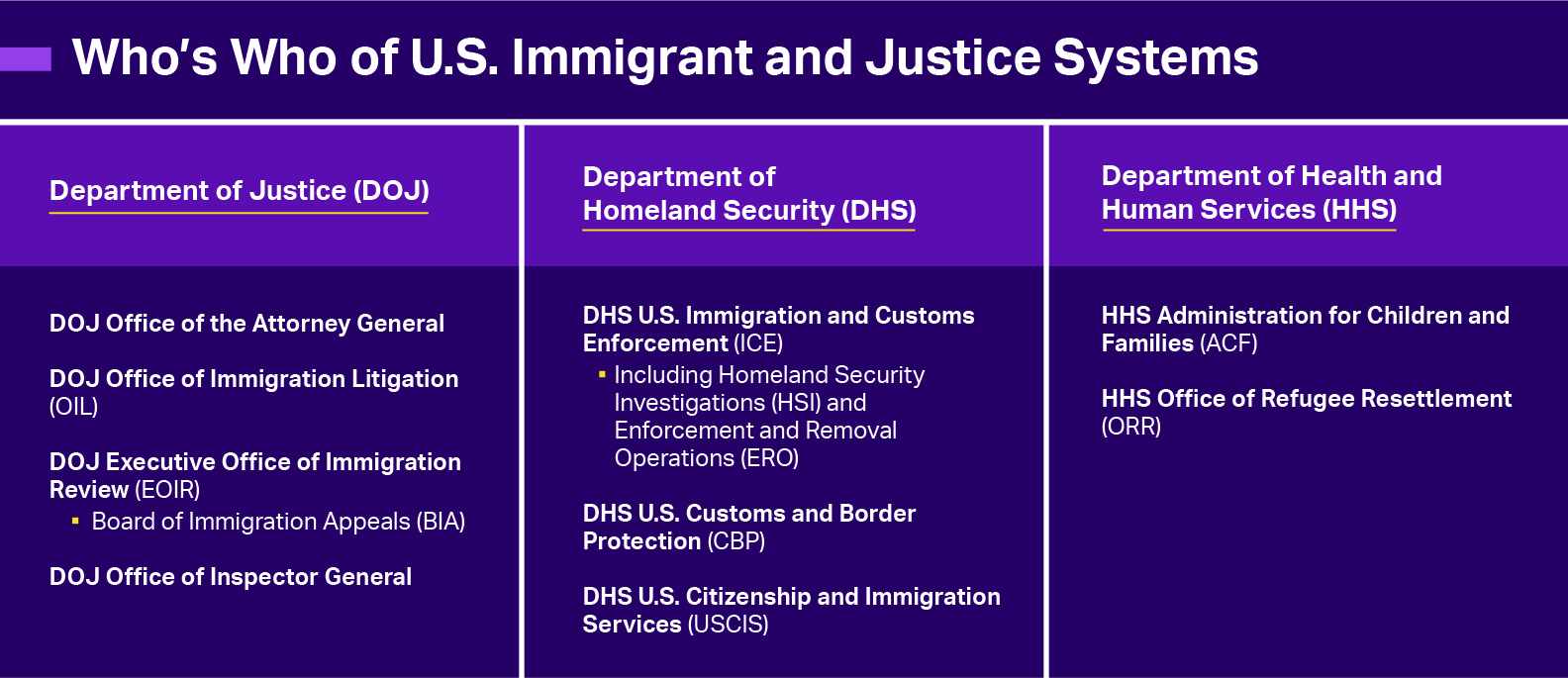

An Overview of the Federal Agencies Comprising the U.S. Immigration System and How They Intersect and Assert Control

Several federal agencies, offices and government contractors comprise the immigration system (See below graphic). This report will provide background on each agency and a landscape of how these practices intersect regarding reproductive health access and other human rights.

Department of Homeland Security

According to Detention Watch Network, immigration policy began to mirror a punitive criminal justice system in the late 1980s. It was the “War on Drugs” that prompted Congress to amend the Immigration and Naturalization Act to require the mandatory detention of im/migrants with certain criminal convictions. In 1996, two pieces of legislation greatly increased the scope of who could be subject to mandatory detention: the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act and the Illegal Immigrant Reform and Immigration Responsibility Act (IIRIRA).

The wheels were already in motion to stereotype all im/migrants as criminals and were further cemented after September 11th. Following the September 11th attacks, the federal government adjusted its approach to immigration, moving immigration management from the Department of Justice (DOJ) to a newly created Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in 2002. DOJ’s Immigration and Naturalization Service was abolished and three agencies were created under the umbrella of DHS: U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), and U.S. ICE. These three agencies interface the most with migrants, immigrants and asylum seekers. As explained by the Brennan Center for Justice, CBP is responsible for the border and is the entity that separated children from their families under the Trump administration. USCIS processes naturalization and asylum requests. ICE has two primary divisions: Homeland Security Investigations (HSI), which is charged with international criminal operations, and Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO), which handles detainment and deportation.

DHS oversight is conducted by the Office of Inspector General (OIG), also housed in DHS. This office was established in 2002 with a mission “to provide independent oversight and promote excellence, integrity, and accountability within DHS.” This mission is not always clearly executed. The OIG is a Senate-confirmed position nominated by the president, which means that its operations may be subject to politicization. The office itself has faced criticism regarding its leadership and ability to carry out its mission as well as claims of misconduct and politicization.

DHS agencies, particularly ICE, have been fraught with reports of abuse since their very creation. An investigative report by USA Today “revealed more than 400 allegations of sexual assault or abuse, inadequate medical care, regular hunger strikes, frequent use of solitary confinement, more than 800 instances of physical force against detainees, nearly 20,000 grievances filed by detainees and at least 29 fatalities, including seven suicides,” from 2017 to 2019. The report also analyzed ICE inspection reports from 2015 to 2019 and identified 15,821 violations of detention standards. During this time, over 90 percent of the same facilities received passing grades in inspections. Immigration advocates have rightfully called for the abolishment of this office in recent years, as these flagrant—and unchecked—violations persist.

Department of Justice

DOJ’s Civil Division houses the Office of Immigration Litigation (OIL). OIL oversees all civil immigration ligations and is responsible for coordinating national immigration matters before federal district courts and circuit courts of appeals. OIL attorneys work closely with United States Attorneys’ Offices on immigration cases. OIL provides support and counsel to all federal agencies involved in admission, regulation and removal under U.S. immigration and nationality statutes. The Office is divided into an Appellate Section, a District Court Section, and an Enforcement Section. The Appellate Section oversees civil litigation cases that deal with whether or not someone is subject to deportation and whether an individual is eligible for benefit, relief or protection while remaining in the country. The Appellate Section works closely with the State Department, USCIS, ICE and CBP.

Cases handled by OIL shape the climate in which refugees may seek asylum. For example, in Wang v. Lynch (2015), the Seventh Circuit Court ruled that citizens could claim persecution and be eligible to seek asylum in the United States from countries implementing coercive population control programs. While Meng v. Holder, in the Second Circuit, held that those who assisted in persecuting others within coercive population control programs were ineligible for asylum. In Avendano-Hernandez v. Lynch (2015), the Ninth Circuit Court held that a Mexican transgender woman should be granted Convention Against Torture (CAT) protection on the basis that she was tortured by Mexican police officers due to her gender.

The Executive Office of Immigration Review (EOIR) adjudicates immigration cases and handles cases involving detained individuals and asylum seekers. Though the U.S. has a checkered history of compliance with international human rights law, it is a party to numerous international treaties that uphold refugee and asylum rights, beginning with the Convention on the Status of Refugees. This governing convention for international human rights law lays out all persons’ rights to “enjoy fundamental rights and freedoms without discrimination.” The U.S. is also a party to the Convention against Torture, which obligates host countries to not return a person to a country where they believe they are in danger of being subjected to torture. Many fleeing persecution because of gender identity or expression are protected to this end under international law. EOIR should comply with and uphold these protections.

The Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) is housed within EOIR and “is the highest administrative body for interpreting and applying United States immigration laws.” The main function of the BIA is to review appeals rendered by immigration judges and DHS district directors. This is primarily done by paper review, but on rare occasions, the BIA may hear oral arguments at EOIR headquarters in Falls Church, Virginia. Although BIA decisions are binding on all DHS officers and immigration judges, their decisions can be modified or overruled by the attorney general or in federal court. The BIA consists of 23 appellate immigration judges and up to two deputy chief appellate immigration judges.

Department of Health and Human Services

The United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) houses the Administration for Children and Families (ACF), which houses the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR). ORR’s mission is to provide new populations with assistance acclimating to America. Their programming includes resources, benefits and services for the following groups as listed on ORR’s website: eligible refugees, asylees, Cuban/Haitian entrants, special immigrant visa holders, Ameriasians, victims of trafficking and unaccompanied children who enter the country without an adult parent or guardian. ORR’s programming for unaccompanied children is housed in two programs: the Unaccompanied Refugee Minors Program (URM) and the Unaccompanied Children Program.

Most eligible populations have to go through an application process for placement and services offered through the URM program unless their refugee status has been identified overseas or they are a class of refugees referred by the State Department. Once approved, they may be placed in foster care, receive case management, financial support, family tracing and reunification, healthcare (including dental and mental health care) and other services. Placement services are managed by the Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service and the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops.

Unaccompanied children are defined as persons who have no lawful immigration status in the United States, are under 18 years of age and have no parent or legal guardian in the United States physically present that is available to provide care and physical custody. Once unaccompanied children are taken into custody, they are transferred to ORR in “the least restrictive setting,” that is, according to ORR, in the best interests of the child. According to their website, “ORR has provided care for and found suitable sponsors for almost 409,585 unaccompanied children.” The majority of unaccompanied children are placed through a network of state-licensed care providers funded by ORR. Pro bono legal representation or counsel is, to the greatest extent practicable, made available to unaccompanied children.

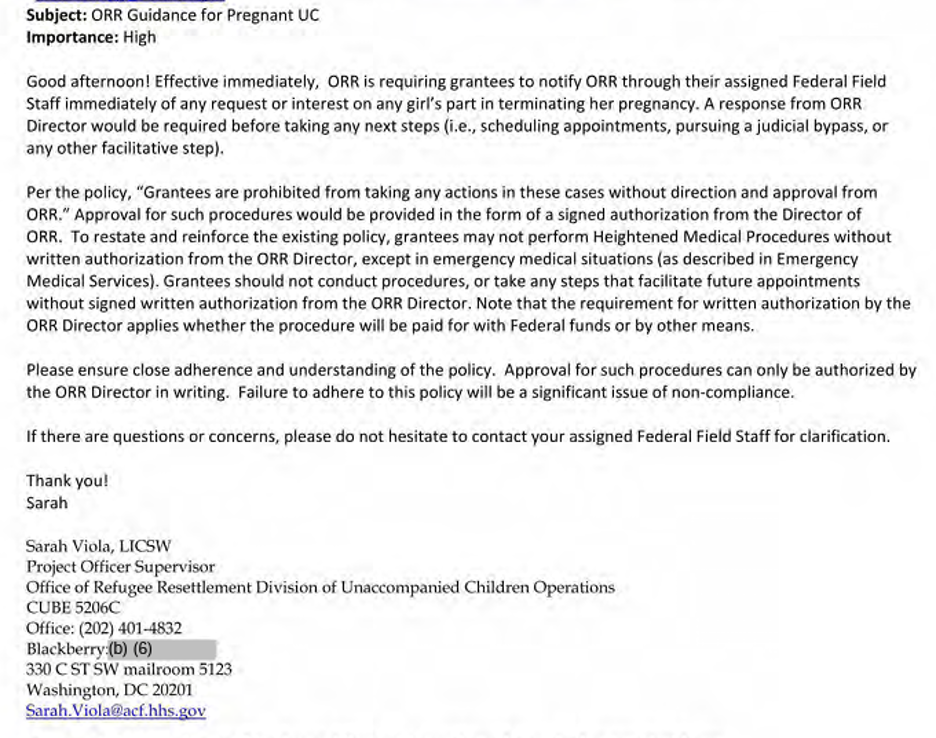

Under the Trump administration, ORR—along with ICE—was charged with the responsibility of many minors who had been separated from their parents. HHS began overtly denying the minors under their control their constitutional right to abortion. In March 2017, an HHS ORR official emailed HHS ACF staffers laying out the department’s “new guidance” for pregnant, unaccompanied children—requiring grantees to notify ORR of abortion requests immediately. Equity Forward obtained a copy of this communication via public records litigation (below).

Image 1. March 2017 Email Sent by HHS ORR Official Sarah Viola

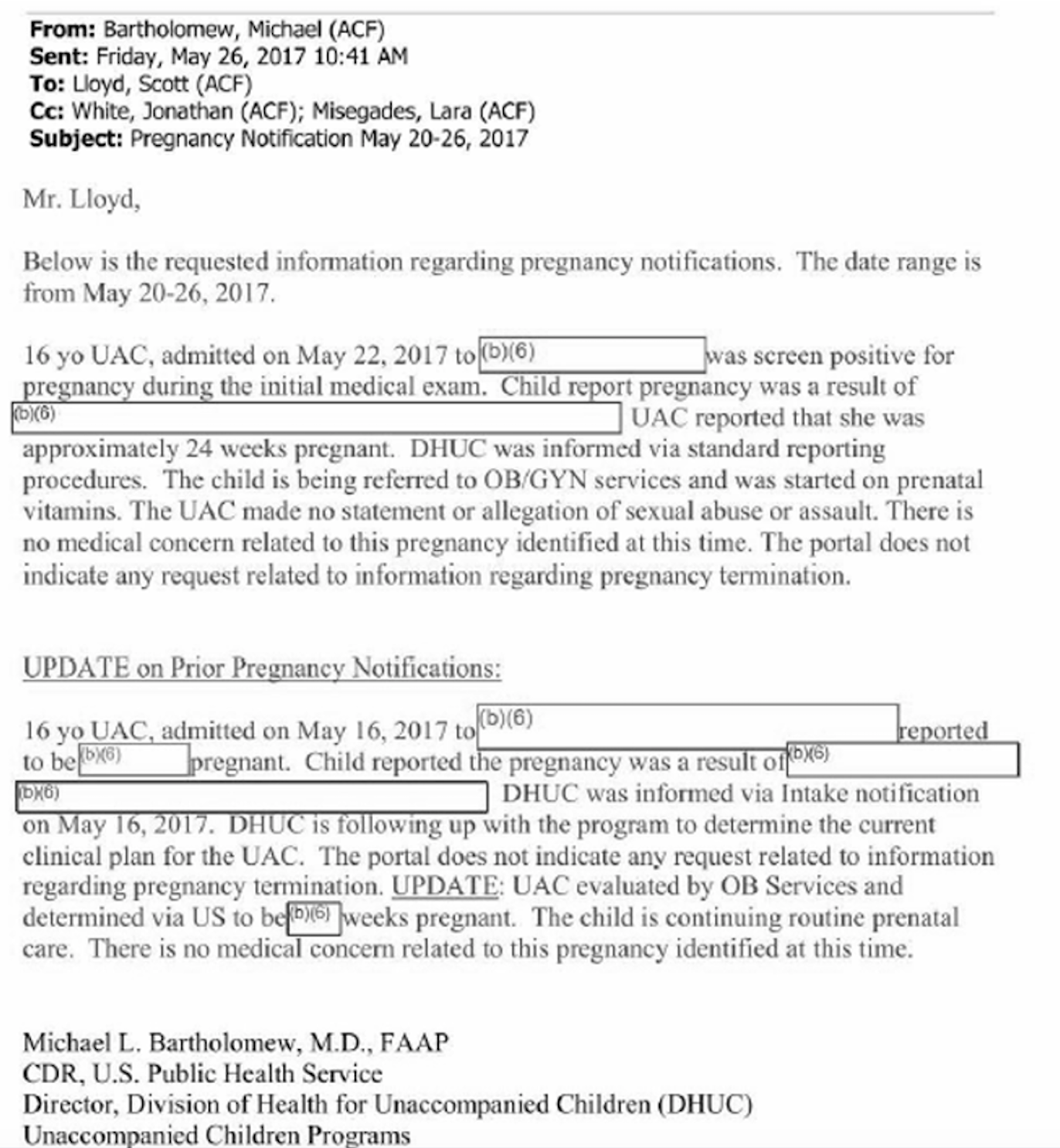

The extent to which the U.S. government, under the Trump administration, would go on to personally interfere with im/migrant teens’ abortion care was ludicrous. Beginning in May 2017, former ORR Director Scott Lloyd requested and received weekly spreadsheets of pregnant teens in his office’s care and personally tried to block their requests for abortions. According to public records obtained by American Bridge, Lloyd tracked the girls’ menstrual cycles. As evidenced in emails obtained by Equity Forward through public records litigation, the reports also included information on each minor’s gestation, background on how they got pregnant and any medical issues.

Image 2. May 2017 Email from HHS ACF Official Michael Bartholomew to HHS ORR Director Scott Lloyd Outlining Updates to a Pregnancy Report

The U.S. Immigration System and Systemic Failures to Provide Access to Health Care

Reproductive Health Care

The U.S. immigration system’s treatment of im/migrants when it comes to reproductive health care can appear contradictory. On one hand, U.S. agencies routinely deny voluntary access to abortion and birth control, appearing to favor pregnancy. On the other hand, they engage in involuntary practices of sterilization through coercion and without consent, and fail to support healthy pregnancies. The practices are, however, incredibly consistent, as the underlying motivation is to wield control and determine who has agency and autonomy.

From a lack of provision of basic family planning services, such as birth control, to coercion and blocking people from their constitutional right to abortion to forced sterilization within U.S. government detention centers, access to reproductive health care and reproductive freedom are often denied. This denial begins with a lack of communication to those detained that reproductive health care services are even an option.

“A major barrier for reproductive care in detention is the fact that the facilities themselves often don't tell immigrants their rights to reproductive care. So many of our clients find out they are pregnant when they are taken into DHS or ORR custody, but then not told that abortion is legal in the U.S. and they have a right to both continue or to terminate their pregnancy,” explained Rosann Mariappuram of Jane’s Due Process.

This secrecy around actually accessing reproductive health services has been corroborated by many accounts. A 2009 ACLU report entitled “Don’t Tell and They Won’t Ask” referenced original interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch (HRW) with ICE officials and detained people: “Basic services and options related to reproductive health, including emergency contraception, prenatal care, post-partum care, and abortion, are … available to some detainees, at some facilities, under some circumstances, if you know who, and how, to ask.” ICE officials told HRW that emergency contraception and abortion could be accessed, but they were not explicitly offered or provided to people detained by the agency. One detained interviewee told HRW, “If I had the option I would have [had an abortion] … I didn’t know that there were those kind of services available.”

Mariappuram added, “Several of our former clients were part of a class action lawsuit filed by the ACLU to stop this type of interference by DHS, and won.” Coercion on the part of staff, sometimes employed by government contractors with anti-abortion ideologies, is also an issue. Mariappuram continued, “However, we have to remain vigilant because we still frequently deal with shelters (often run by religious organizations) or individual staffers who refuse to tell unaccompanied immigrant minors about their rights. We also sometimes get contacted by adults in detention facilities like Hutto or Pearsall who are pregnant and trying to seek care. In those instances, we work with local abortion funds and legal counsel to get them abortion care or released on parole so they can seek care outside of the facility.” This can be logistically challenging for many reasons—including, as a Center for American Progress report notes, because many detention centers are in rural areas that lack access to abortion providers.

This type of interference with federal officials failing to tell im/migrants about their rights to reproductive health care is devastating when it comes to abortion—a procedure for which time is of the essence. Delays are compounded by state-level restrictions to abortion care—which are plentiful in the southern states that house the majority of U.S. immigrant detention centers and are extremely hostile to reproductive rights (Texas claims the most detention centers and just passed the most extreme abortion ban in the country). Based on where their detention center is housed, im/migrants are subject to state-level restrictive laws mandating parental consent, waiting periods, mandatory ultrasounds, gestational bans and more.

Of course, paying for abortion procedures is another barrier. U.S. detention centers are barred from providing detained people abortions due to the Hyde Amendment, which has been reauthorized each year since 1976 to prohibit the use of federal funds for abortion care. Proposed legislation to allow for the provision of abortion services in detention centers has been struck down in Congress; the Senate has just blocked the House’s elimination of Hyde in the 2021 spending bill. The cost of care pushes abortion out of reach for many im/migrants in government custody.

As HRW’s interviews with detained or recently detained women demonstrated, the denial of reproductive health care to those who are detained is by no means limited to abortion, either. Interviewees described being denied gynecological care, even in cases where they had histories of abnormal pap smears. Detained people also told HRW that they were denied birth control while detained, even in extreme cases where the medication had been prescribed to manage heavy bleeding. A pregnant woman with an ovarian cyst that her doctor said should be monitored every two to three weeks never received care in detention and was instead told to “be patient.” Interviewees told stories of having to beg for even basic sanitary pads so as not to bleed through their clothes while menstruating. As Lucie Arvallo of the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Justice put it, “Detention facilities have proven to be wholly inadequate and inhumane providers of reproductive and sexual health care, even for the most basic services.”

Thanks to Dawn Wooten’s whistleblowing of the atrocities at ICE’s Irwin County Detention Center, we are aware of the practices of forced sterilization that are still happening within U.S. detention facilities, denying ultimate reproductive autonomy to people. Despite the Biden Administration’s pledge to close Irwin, The Intercept reported that as recently as June 2021 detained people were still being sent there.

Nearly all respondents to our survey emphatically responded that they believe abuse at the Irwin County Detention Center is part of a broader problem/pattern. Arvallo expressed to Equity Forward, “The horrendous abuses suffered by the detained women in ICE custody at the Irwin County Detention Center in Georgia are very much intertwined with this country’s racist and xenophobic history of controlling the bodies and reproductive agency of people of color. From forced sterilization campaigns targeting Black and Brown women last century to the forced hysterectomies performed on the im/migrant women in ICDC custody, this country has often taken away the right of women of color to make their own reproductive decisions.” She continued, “The Department of Homeland Security has long failed to protect the people in its custody. Oversight, accountability, and transparency are sorely lacking, with many detention centers boasting a long history of deaths, suicides, sexual abuse, miscarriages, and denial of medical care. Im/migration detention centers are rampant with sexual violence and human rights abuses and are toxic for everyone, but they pose significant and unique risks to individuals seeking reproductive and sexual health care.”

Maternal Health Care

It is not known exactly how many pregnant people seek asylum in the United States, but it is known that more than 4,000 pregnant people were detained by ICE between 2016 and 2018. Detention is a harsh reality for people who are seeking better lives for themselves and their children. During their journey, they may endure treacherous conditions through which they persevere in pursuit of a different future—one they hope will be free from violence and overflowing with opportunity. Unfortunately, what awaits them is oftentimes in stark contrast to the American future they have envisioned for themselves and their families.

Although pregnant people and children are both vulnerable populations, they do not always receive adequate health care once taken into custody by immigration officials. Even as they wait along the border, access to ultrasounds, prenatal vitamins and regular doctor visits are scant. Programming such as Las Zadas exists to help pregnant asylum seekers, but there is no true national safety net for the countless number of people in need of maternal care.

“Many Latinas/xs who have been placed in detention centers are facing abuse and outright denial of adequate prenatal, pregnancy, and abortion care services. The inadequate care that pregnant people receive in detention not only threatens their physical and emotional health, it results in unnecessary harm to their pregnancies. Some detained im/migrant women have been denied medication for life-threatening conditions like preeclampsia and have given birth prematurely, while others have suffered horrendous birthing conditions, including being shackled during the birthing process. Many detained mothers are not producing enough breast milk because they’re not getting enough food and water,” said Lucie Arvallo of the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Justice.

In 2011, ICE released its first Operations Manual ICE Performance-Based National Detention Standards (PBNDS) as an attempt to revise detention standards and step toward detention reform. PBNDS, which was revised in 2016, standards are applicable to “service processing centers, contract detention facilities, and state or local government facilities used by ERO through Intergovernmental Service Agreements (IGSAs) to hold detainees for more than 72 hours.” The ICE manual for detention standards consists of 300+ pages, yet a little under two pages is dedicated to directions for caring for pregnant people. Within those few paragraphs, it states that pregnant detainees should be given close medical supervision, have access to prenatal care, specialized care and comprehensive counseling inclusive of opportunities to learn parenting skills, family planning and abortion services. It also states that “pregnancy management and outcomes shall be monitored quarterly through a continuous quality improvement process,” and that the use of restraints must be due to “(a) a medical officer has directed the use of restraints for medical reasons; (b) credible, reasonable grounds exist to believe the detainee presents an immediate and serious threat of hurting herself, staff or others or reasonable grounds exist to believe the detainee presents an immediate and credible risk of escape that cannot be reasonabl[y] minimized through any other method.” According to the PBNDS, restraints during active labor or delivery are not permitted. Mental health assessments must be offered to any detainee who has been pregnant and given birth, miscarried or terminated a pregnancy in the past 45 days.

Although the guidelines are clear, the lived experiences of pregnant asylum seekers and im/migrants do not reflect a system that adheres to PBNDS standards. The few protections afforded to this group came under fire during the Trump administration, which chose to reverse a policy that prevented pregnant people from being detained for long periods and also instated Migrant Protection Protocols that left pregnant asylum seekers stranded in Mexican border cities. A brief authored by the Center for Reproductive Rights, the American Friends Service Committee, Human Rights First and the Women’s Refugee Commission details the multiple ways in which our immigration system has failed and abused pregnant im/migrants and asylum seekers during the pandemic in particular.

The immigration system places additional stressors related to immigration status on pregnant and birthing undocumented people, which can block them from receiving the health care they need during pregnancy. “Combined with state restrictions, economic barriers, and a host of other obstacles, this climate of fear and uncertainty is impacting the decisions of im/migrants who need access to the full range of reproductive health care, including abortion care, which becomes more expensive and harder to obtain when delayed. Pregnant people who are worried about deportation are also skipping out on prenatal appointments and many are waiting until they are in labor to go to the doctor. As a result, life-threatening conditions such as preeclampsia are not diagnosed until patients experience seizures. This is especially concerning because for many women with low incomes, OB-GYN appointments are their only regular visit to the doctor and an entry point for a range of preventive care from checking blood pressure levels to screening for breast and cervical cancer,” said Lucie Arvallo of the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Justice. Additional fear of violating the “public charge rule” made access to community health clinics, free medical care and other government support that exist to provide access to necessities out of reach for many people who would stand to benefit from such help.

Health Care for Minors

The Biden administration renewed Title 42—a public health order used under the Trump administration that allows border agents to quickly kick out or block im/migrants from entry before they are able to seek asylum—in early August 2021. Concurrently, expedited removal—deportation without a hearing in front of an immigration judge—is being used to deport families who cannot be removed under Title 42. U.S. CBP data show that 341,327 family units and minors (unaccompanied and accompanied) have been encountered at the U.S.-Mexico border this fiscal year. Title 42 had been authorized to expel 25 percent of these people. And although President Biden issued an executive order in February 2021 requesting that DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas and Attorney General Merrick Garland review the U.S. asylum system within 180 days, in August 2021 the administration acknowledged that the deadline would not be met.

This is also a crisis disproportionately impacting young people. Those detained by ICE, on average, are just 28 years old, with children making up 17 percent of the population. Minors who are apprehended by immigration officials and even those allowed to remain in the country still face many barriers to safe family environments that are vital to their development. The Trump administration was heavily critiqued for its role in forcibly separating children from their parents and guardians. A 2019 issue brief from the HHS OIG reported that nearly 3,000 children had been separated from their loved ones and yet a total estimate was impossible to report since, prior to 2017, accounting was not required. The toll separation has on children is devastating. A report from HRW includes anecdotes of children who were cruelly ripped from their siblings, grandparents, aunts and uncles; of their parents’ notes’ releasing guardianship to their accompanying adult being rejected; of being separated from their parents without any idea where they may be or whether or not they are still alive. Efforts are being made to reunite some of these families, though they remain ongoing; their separation should never have happened and will forever remain a dark moment in U.S. history.

For many minors, being separated from their families is just the beginning of more hardship. The HHS ORR is tasked with providing shelter and care for refugee children, but their facilities and the way they are run have been found to be inadequate and abusive. An investigation by Reveal from the Center for Investigative Reporting found several incidents of law enforcement being used to address mental health crises and behavioral issues of children housed in these shelters. An example of this is a 16-year-old boy being tased for breaking shelter property because he did not want to go to school that day. The boy had bounced around five refugee shelters in the previous nine months. It can be assumed that mental health services would have been a better response than the involvement of law enforcement.

Between the Trump administration’s inhumane family separation policy and its interference with minors’ reproductive health care, young people have been particularly imperiled within the U.S. immigration system in recent years. As was the case with Jane Doe outlined in the above HHS section, Rosann Mariappuram of Jane’s Due Process outlined how state-level parental consent laws can be devastating for those in U.S.-government custody. “If you are under 18, Texas requires you to obtain the consent of a parent or guardian to get an abortion. Most youth who can safely involve a parent in their decision do so. But for teens who don't have a parent in their life, are living through emotional or physical abuse at home, or who are in the custody of the foster care system or immigration detention, they are forced to obtain a judicial bypass, which is special permission from a judge to consent to your own abortion care. From our work, we know that the most marginalized youth are hurt by parental consent laws, including immigrant youth, LGBTQIA+ youth and youth of color, especially Black and Latina teens in Texas.”

The denial of reproductive health care services to these teenagers is not exclusive to abortion or the Trump administration. A 2017 National Women’s Law Center report lays out the various ways in which unaccompanied minors are particularly vulnerable in U.S. government detention centers. Emergency contraception, birth control and STI treatment are among other forms of health care denied to young people, often by the (sometimes religiously affiliated) organizations that the government is contracting to run its shelters and provide services.

Access to Inclusive Quality Health Care Generally

Access to quality healthcare, inclusive of non-discriminatory, gender-affirming care, is a human right. Yet there are numerous allegations, accounts and official reports detailing inadequate healthcare in detention centers and care being inaccessible to immigrant communities. As Lucie Arvallo from the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Justice stated, “These physical and policy barriers for im/migrants accessing health care, particularly for those who are undocumented, places im/migrants at higher risk for preventable illness and long-term negative sexual and reproductive health outcomes.”

In September 2020, the House Committee on Homeland Security released a report detailing multiple failures to meet basic standards of care in ICE facilities. The report pointed to a lack of DHS oversight, inspections conducted by an inadequate contractor, a faulty corrective action plan and minimum enforcement that each contribute to a faulty system of care. The Committee chose to detail four areas in which facilities failed to meet basic standards of care: 1) deficient medical, dental and mental health care, including lack of protection from COVID-19; 2) misuse and abuse of solitary confinement as a form of retaliation; 3) challenges accessing legal and translation services; and 4) unsanitary conditions, such as standing water in housing units.

Medical negligence, preventable deaths, and inadequate care abound in ICE facilities, even as the agency claims to spend “more than $269 million annually on the spectrum of healthcare services provided to detainees.” A Washington Post article amplified the above-mentioned committee report, which included details of a man going into anaphylactic shock four times in four months as a result of a peanut allergy. A report by the Southern Poverty Law Center found that diabetics do not have access to meals that meet their nutritional needs, drinking water is not always safe and infections contracted in facilities have led to paralysis and death, among many other incidents of medical negligence and abuse. A report by the ACLU details multiple first-person accounts from people who were detained regarding the hazardous conditions in which they were forced to live. Within their report are stories of ibuprofen being used to treat both snake bites and gout; of people living with HIV having to wait two months for medical treatment; of requests for mental health care being ignored; of people being denied wheelchairs; of disabled persons being sedated and hidden during inspections; of increased incidence of suicide; of solitary confinement being used as retaliation; and of people in need of cancer treatment receiving dangerously inadequate care.

According to their fiscal year 2020 report, the ICE Health Services Corps (IHSC) provides direct care through ICE-owned facilities; oversees care for ICE detainees housed in contracted facilities; reimburses off-site health care services detainees receive while in ICE and U.S. CBP custody; and supports special operations missions. IHSC is also responsible for publicly reporting in-custody deaths within 90 days. There is an obvious gap between what IHSC is charged with doing and what is actually being done, as the health and lives of countless detained migrants are placed in danger.

The American Medical Association (AMA) has been a vocal advocate for the health and safety of those detained in detention centers. Their statements have called for support of humanitarian standards for those in CBP custody, urged DHS and CPB to address conditions in facilities at the southern border and requested congressional oversight hearings regarding the care of families in DHS-run detention facilities. AMA has also joined other medical professional societies to raise concerns about CBP’s expiring contract for medical services. Their advocacy efforts resulted in CBP renewing its contract with Loyal Source Government Services LLC through February 2021, with the possibility of extending through September 2022.

In addition to the conditions within the facilities themselves, the rural location of many detention centers makes it difficult, and oftentimes impossible, to access emergency care in a timely manner. Access to specialized care is often difficult for the same reasons. In 2019 the Southern Poverty Law Center, along with other non-profit organizations and a law firm, filed a class action lawsuit asking the federal court to ensure ICE provides adequate monitoring and oversight to improve healthcare for detained people. Some of the plaintiffs in the lawsuit were detained in rural areas of California. The L.A. Times reported accounts from detained people: Abdullah Draihat was denied vision surgery while detained at an Adelanto ICE Processing Center near Victorville, resulting in his condition worsening beyond repair. Marco Montoya Amaya had not received treatment for an invasive brain parasite while detained at a center near Bakersfield. Luis Manuel Rodriguez Delgadillo missed court dates due to a lapse in mental health care while detained at Adelanto.

The COVID-19 pandemic presented additional health challenges within detention facilities. A Government Accountability Office report found that despite ICE developing protocols to address the new standards necessitated by pandemic mitigation, efforts such as quarantine and social distancing were not always correctly implemented. As facility inspector Dr. Carlos Franco-Paredes shared with the New York Times, several factors were to blame for surges of the virus within detention centers, namely, “transfers of detainees between facilities, insufficient testing, and lax Covid-19 safety measures.” Raudel, an asylum seeker from Cuba, shared in an NPR article that detainees who tested positive were “put together in one room.” His experience substantiates claims of improper adherence to safety protocols. An ACLU report features stories of people released from ICE facilities during the pandemic. Their stories echo one another: accounts of maskless ICE employees and medical staff, inadequate amounts of sanitizer and soap, detained individuals not being offered masks or being given just one mask to use indefinitely, limited testing and medical care, nonexistent social distancing, improper care of high-risk individuals and symptomatic individuals not receiving proper medical treatment. It is unclear how the pandemic can be mitigated within ICE facilities, especially since the agency continues to shuffle detained individuals from facility to facility, which poses an infection risk to those detained as well as the surrounding communities. Efforts to roll out a vaccination plan for those apprehended or detained have been delayed and without much success.

Even when people are released from custody, the presence of ICE permeates immigrant communities as a blockade to health care. As Rosann Mariappuram from Jane’s Due Process said, “There is also often the fear of police presence at healthcare facilities that do exist, and because Texas passed SB 4, police in our state are allowed to ask for proof of immigration status, effectively weaponizing themselves as agents of ICE.”

Detained Populations of Color and People who are LGBTQIA+ and/or Undocumented Affected Most Adversely by the U.S. Immigration System

This is a crisis targeting communities of color. The U.S. immigration system is designed to harm especially Latino/x and Black im/migrants; it discriminates against LGBTQIA+ people, particularly transgender folks. Undocumented communities are terrorized. Sexual assault survivors, non-English speakers, those with disabilities and young people (as the above Health Care for Minors section outlined) are also adversely and negatively affected. Many of the most marginalized groups experience compounded and interlocking oppression, some based on intersectional identities. While by no means exhaustive, this section aims to name some of the people who suffer the most through the immigration system. The following sections will interweave their experiences regarding particular health care abuses within the system.

Latino/x, Black, Indigenous, AAPI and Communities of Color

As explained in the above sections, the U.S. immigration system suffers from a white supremacist structural design. America’s laws criminalizing im/migration have long been based on race. As law professor Alina Das has researched, the roots of today’s immigration law can be traced back to the Fugitive Slave Laws and states’ efforts to police the migration of free Black people in the mid-1800s. As Das explains, these tactics influenced the 1875 Page Act to deter first Chinese im/migrants, then other non-European groups, from entering the United States—and continued to build a legal framework to preserve whiteness.

Indeed, the majority of 500,000 im/migrants typically detained at once by ICE are Latino/x (which may include those who identify as Afro-Latino/x). Demographic data for the ICE-detained population is limited: a 2018 American Immigration Council report synthesized three different datasets (two of three created with data obtained by FOIA) to give us a better idea of who is being held in U.S. custody. The report found that 43 percent of those detained by ICE (as of 2015) are from Mexico and 46 percent are from Central America’s Northern Triangle region (El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras). Another 5.5 percent came from South America, with the remaining 6 percent split between the Asia Pacific region, Africa, Europe and North America (with the lattermost category amounting to the smallest group of 1.1 percent). More comprehensive data that can distinguish not just im/migrants’ country of origin, but also race and/or ethnicity, is needed. As we will discuss below, data should be inclusive of sexual orientation and identity, as well as characteristics like disability.

Lucie Arvallo, National Latina Institute for Reproductive Justice, explained: “Latinas/xs face structural barriers that serve to undermine our rights and uphold injustices. These barriers are rooted in racist, xenophobic, and misogynist ideology reinforced by government policies, carceral institutions, and even in our own homes and communities. As a result, Latinas/xs have less access to reproductive healthcare, experience poorer health outcomes, and face significant obstacles to achieving our full economic, social, and political power.”

Arvallo continued, “These barriers are compounded for individuals who are detained, especially for Black, Indigenous, Latinx, and Asian [American and Pacific] Islander im/migrants and im/migrants who are gender non-conforming and transgender. In detention, individuals are often faced with horrendous conditions and human rights abuse, with limited access to comprehensive health services, clean food and water, and basic hygiene and sanitary products. Detention tears an individual [a]way from their family members, support system, and trusted health care providers, increasing isolation and the risk of long-term negative mental and reproductive health consequences. The use of punitive, jail-like facilities to detain im/migrants as they await their legal proceedings has had a devastating impact on communities of color, has further empowered the private prison industry, and has wasted precious government resources that could have been used to build, not tear down, our communities.”

The U.S. immigration system, aided and abetted by U.S. law enforcement, adversely discriminates against Black people. According to the NAACP, a Black person in the United States is five times more likely than a white person to be stopped by police without just cause. Overpolicing, hand in hand with harmful policies like the 287(g) program, allows local police forces to transfer im/migrants they have detained over to ICE, where they can face deportation. Deportation disproportionately affects Black im/migrants. As analyzed in the State of Black Immigrants 2020 report put out by Black Alliance for Just Immigration (BAJI) and NYU Law’s Immigrant Rights Clinic, “Although Black immigrants comprise just 5.4 percent of the unauthorized population in the United States, and 7.2 percent of the total noncitizen population, they made up a striking 10.6 percent of all immigrants in removal proceedings between 2003 and 2015.” The report also found that while Black immigrants make up only 4.8 percent of detained immigrants facing deportation before the EOIR, they comprise 17.4 percent of those who are facing deportation on criminal grounds.

According to the Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services (RAICES) data from the Karnes County Residential Center, there was a higher proportion of Haitian im/migrants in ICE custody than any other nationality in 2020. Even as ICE released some families due to the COVID-19 pandemic, between 29 and 44 percent of the center’s detained people were Haitian. One reason for this could be higher bails for Black detained people. RAICES’ bail fund, on average, pays $10,500 to release an immigrant from ICE detention. The average bail cost for a Haitian immigrant, on the other hand, is $16,700. A 2020 study found that Black immigrants are six times more likely than other detained people to be held in solitary confinement by ICE.

LGBTQIA+ Populations, Especially Transgender People

We lack comprehensive data to accurately quantify detained LGBTQIA+ people in the U.S. immigration system. In 2017, Rep. Kathleen Rice (D-NY) requested and received more information to this end from ICE. That year, 0.14 percent of those detained by ICE self-reported being LGBT. We are missing data to encompass all gender identities, as data is obtained largely using gender binaries (ICE-reported statistics tell us that almost eight in 10 detained people are men). While more inclusive data are needed to fully understand the demographics of detained populations, we acknowledge that such data can be weaponized to further harm vulnerable populations, particularly transgender people. We recommend that ICE implement gender-inclusive terminology for self-identification in all of its intake forms and data collection methods while also making data publicly available so that independent, human-rights-focused organizations can effectively monitor and advocate for those in ICE’s custody. The Human Rights Campaign has guidance for the best self-identification data collection practices for LGBTQIA+ people, as does the Office of the United Nations (UN) High Commissioner for Human Rights, which emphasizes a “do no harm” approach administered by human rights civil society groups.

The data we do have, as well as accounts from survivors of the immigration system and organizations working on their behalf, illustrate the reality that transgender and gender non-conforming people in particular suffer within the U.S. immigration system. The Center for American Progress analyzed the same ICE report to Rep. Rice, which disclosed that while just 0.14 percent of people the agency detained that year identified as LGBT, 12 percent of sexual assault and abuse cases within the detention centers targeted LGBT people. This abuse is particularly prevalent for transgender and gender non-conforming people. Kris Hayashi of the Transgender Law Center told us, “Detained trans and gender non-conforming people are disproportionately impacted by lack of access to care due to systemic transphobia and homophobia which also results in high rates of violence, harassment, assault and abuse in detention this is even more so for trans Black and Brown people.”

ICE detains transgender women in 17 facilities—four of which are all-male facilities, 13 of which are mixed-gender (where we do not know if transgender people are being detained with others based on their gender identity). In recognition of how vulnerable transgender people are in detention, ICE established new guidelines for detaining trans people in 2015. The agency has since attempted two dedicated units for transgender women in recent years. Unfortunately, these centers have not proven safer for trans women detained there.

The first facility—opened in 2014 within the Santa Ana City Jail in California—was run by a massive private prison contractor, CoreCivic. By this point, CoreCivic’s medical neglect at its facilities had been revealed and the federal Bureau of Prisons had ceased working with the company. Immigrant rights groups, including Community Initiatives for Visiting Immigrants in Confinement (CIVIC), filed a federal complaint that transgender women “were subject to unlawful and degrading strip searches at the Santa Ana Jail.” HRW released a 2016 report featuring interviews with 28 transgender women detained by ICE between 2011 and 2015. Even those detained in segregated units in Santa Ana described abusive strip searches by male guards. They were also unable “to access necessary medical services, including hormone replacement therapy, or have faced harmful interruptions to or restrictions to that care; and have endured unreasonable use of solitary confinement.”

By 2017, ICE had shut down the transgender unit in Santa Ana. The same year, they established a transgender unit at the Cibola County Correctional Center in New Mexico—also operated by CoreCivic. The same issues persisted. After a few years of operation, The Santa Fe Dreamers Project outlined the abuse of transgender women there: “Medical neglect, lack of mental health services, poor conditions of detention, and abuse of solitary confinement was rampant at Cibola”. Most devastatingly, in May 2018, Roxsana Hernandez Rodriguez, an asylum-seeking transgender woman held at the Cibola County prison, died of HIV-related complications. An independent autopsy later revealed that Hernandez showed signs she had been abused before her death, raising questions about her care at the facility. In January 2020, ICE shut down Cibola—and promptly transferred many of the women to a detention center in Tacoma, Washington, that houses cisgender men. A little over a year after Hernandez’s death, Johana Medina León, another asylum-seeking transgender woman, died in a hospital in El Paso, Texas, shortly after being released from ICE custody at the Otero County Processing Center (run by another private contractor, Management and Training Corporation). She reportedly requested medical attention while in custody but was denied.

Hayashi said, “This abuse is definitely part of a larger pattern and system. For trans people, being detained and denied care absolutely interferes with their health, for trans people already receiving hormone therapy for example, being denied that care is hugely detrimental to their mental and physical health.” To this end, immigrant rights and LGBTQIA+ rights activists are working to end transgender detention as part of a broader quest for the abolishment of immigrant detention. In the face of the COVID-19 pandemic in April 2020, the Transgender Law Center filed a class action lawsuit in the District of Columbia to free all transgender people detained by ICE.

Undocumented Communities

Fear of detention, fear of deportation and fear of family separation severely hinder access to quality health care, including reproductive health outside of the walls of detention centers—particularly for those who are undocumented and living within the United States. These barriers take the form of state restrictions, economic barriers and other obstacles, including checkpoints and police intimidation. As Rosann Mariappuram of Jane’s Due Process outlined, “In Texas, many undocumented folks or mixed status families are required to travel across the state (and through border check points) to get to an abortion clinic, birth control clinic, or place where they can seek preventative care like mammograms or pap smears. There is also often the fear of police presence at healthcare facilities that do exist, and because Texas passed SB 4, police in our state are allowed to ask for proof of immigration status, effectively weaponizing themselves as agents of ICE.”

Worryingly, as Lucie Arvallo of the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Justice put it, “The threat of detention, family separation, and deportation for themselves or members of their families is having a chilling effect on im/migrant communities and leading many Latinas/xs to avoid reproductive health care altogether.”

Arvallo continued, “According to a survey we conducted with PerryUndem in 2018, this is having a severe community impact, with one in four respondents (24%) indicating they have a close family member or friend who has put off getting health care because of fear around immigration issues, and one in five (19%) saying the same about reproductive health care. Combined with state restrictions, economic barriers, and a host of other obstacles, this climate of fear and uncertainty is impacting the decisions of im/migrants who need access to the full range of reproductive health care, including abortion care, which becomes more expensive and harder to obtain when delayed. Pregnant people who are worried about deportation are also skipping out on prenatal appointments and many are waiting until they are in labor to go to the doctor. As a result, life-threatening conditions such as preeclampsia are not being diagnosed until patients experience seizures. This is especially concerning because for many women with low incomes, OB-GYN appointments are their only regular visit to the doctor and an entry point for a range of preventive care from checking blood pressure levels to screening for breast and cervical cancer … These physical and policy barriers for im/migrants accessing health care, particularly for those who are undocumented, places im/migrants at higher risk for preventable illness and long-term negative sexual and reproductive health outcomes.”

In a carceral state with a healthcare system that already poses significant barriers to immigrants accessing its services, detainment makes that access virtually impossible. It strips people who are detained of their autonomy and right to safe and culturally affirming health care.

Conclusion

Im/migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees coming to the United States are seeking a better life. A better life with equal and dignified access to the internationally recognized human right to health care and fulfillment of reproductive rights, including abortion care, for all those who choose it. The right to seek and enjoy asylum in other countries is enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted in 1948 following World War II and its accompanying refugee crisis. These rights of im/migrants, asylum seekers and refugees are protected globally. The U.S. government’s failure to comply is a violation of international human rights law as well as many elements of U.S. law. This undue criminalization, detention and reproductive oppression of im/migrants in the United States must stop—beginning with a hard look at the abusive federal agencies that have run rampant with little to no oversight. Increased government transparency, accountability and inclusive data collection, analysis and publication standards are also needed to dismantle the carceral state and chart a different path forward. These challenges to the U.S. detention system are imperative in the fight for sexual and reproductive health, rights and justice for all communities that make up the United States of America.

Molly Bangs is the director at Equity Forward. She is an advocate, researcher, and writer on reproductive health, rights, and justice, as well as other human rights. Molly has a strong background in political research, policy, and journalism, having previously worked as a researcher at Equity Forward, and as an alum of The Century Foundation, The Huffington Post, and the New York City Council. Her bylines appear in outlets including Truthout, VICE, and HuffPost. Molly holds a master’s degree in political science from Columbia University.

Ashley Underwood is a senior researcher at Equity Forward. She is a reproductive justice and public health advocate with an extensive background in working to improve maternal and sexual health outcomes through program implementation and development. Ashley was previously a research associate at Equity Forward; before that, she worked as a research and program manager at NARAL Pro-Choice Ohio. Ashley holds a master’s degree in public health from Case Western Reserve University.

Appendix 1: Survey Respondents

Six partners completed Equity Forward’s survey in June 2021.

Four are non-profit organizations:

● Jane’s Due Process (abortion access for those in immigrant detention; specifically working with unaccompanied minors under the age of 18)

○ Rosann Mariappuram (Executive Director)

● National Latina Institute for Reproductive Justice (Reproductive freedom for Latina/xs; specifically working with Latina/xs living in the United States, with state activist networks in New York, Virginia, Florida and Texas)

○ Lucie Arvallo (Policy Analyst - Immigrant Access to Healthcare and Coverage)

● Transgender Law Center (Litigation and policy advocacy: reproductive health care for detained populations with a focus on transgender people; specifically working with transgender and gender non-conforming people, a majority of low-income people and people of color; national)

○ Kris Hayashi (Executive Director)

● Justice For All Immigrants (Direct representation of detained individuals; specifically working with detained individuals in the Houston, TX area)

○ Jose Luis Martinez (Staff Attorney)

Two are consulting firms that work with non-profit clients across reproductive and immigrant justice spaces:

● Conway Strategic (Messaging for SRHRJ organizations)

○ Yumhee Park (Director)

● KMDB Strategies (Capacity building for reproductive rights, justice, health and immigration organizations)

○ Kaissa Barrow (Founder/Principal)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Kaissa Barrow, who served as an expert reviewer of this project for Equity Forward in a consultant capacity. We would also like to thank every single partner group that took the time out of their busy schedules to meet with us, connect us with other organizations, offer research suggestions and/or complete our survey—as well as for doing the critical work that they do.

‹ Back To Reports